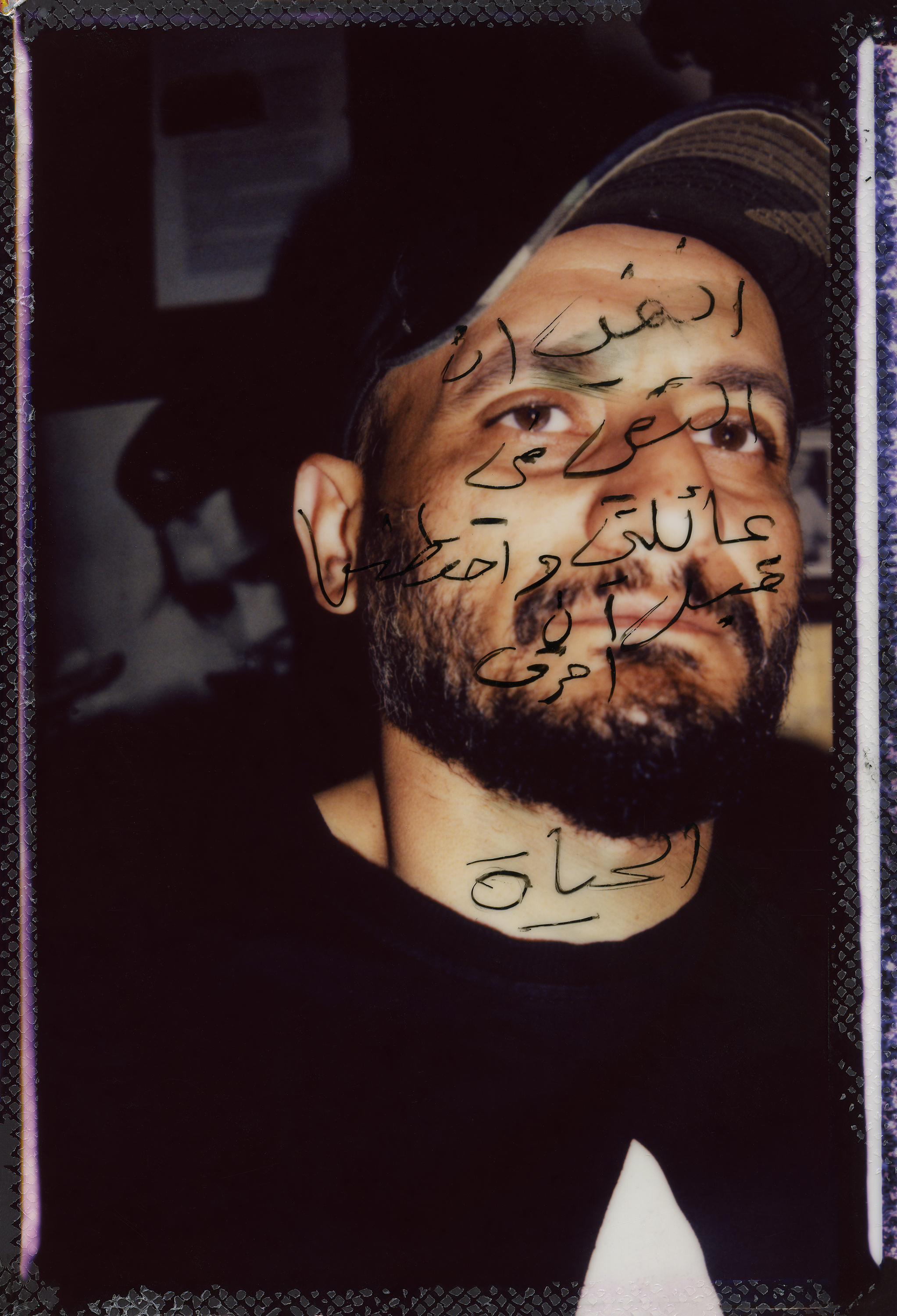

Ibrahim Abdel Qader is a Syrian refugee living in Beirut. His home in Syria was bombed. In this article, Lebanese journalist Al Waled Khalid Yahya writes about Ibrahim’s situation.

“One who loses their home loses their dignity.” So goes a Syrian saying. Ibrahim, a refugee from Syria, adds: “Being deprived of a home, being homeless in exile, robs us of our sense of security. This, combined with a lack of financial security, makes our life a constant struggle to find rent money, so that we do not become homeless again, end up back on the streets again.”

Thirty-eight-year-old Ibrahim Abdel Qader lives with his wife and two children in Sabra, a popular neighborhood in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon. It is a neighborhood inhabited by low-income Lebanese, as well as Palestinian and Syrian refugees, due to the relatively low cost of living compared to other parts of the city. Refugees cannot meet basic life needs or secure a path to a decent future for their children. Their lives have become a struggle to survive. People are unable to think about the future. Their existence is undermined by a lack of security and financial stability. Abdel Qader lives off of a United Nations subsidy of $100 month and the less than $2 he earns working at a coffee shop.

Abdel Qader is a refugee. He has been displaced six times during his quest for asylum in Lebanon. In 2013, his home in the area of al-Qusayr in Syria was bombed. Paramilitary groups make the region a dangerous one.

Abdel Qader says: “I spent nine years drifting from place to place feeling utterly unmoored. Extremely high rents were the reason. Landlords chased me out if I could not pay on time. My home in Syria no longer exists, and it would be extremely risky for me to return.”

For almost a decade now, Abdel Qader has been unable to establish for himself and his children a sense of security. Abdel Qader’s sons attend public school in Lebanon. Hazem is in his first year of middle school and Moataz in his fifth year of elementary school.

Photo: Agata Grzybowska

There is no security without a home. There is no prosperity without stability… On a life full of tears.

Before he was forced from his homeland, Abdel Qader was a farmer with some land of his own. He was able to support his family. He is keenly aware of the reasons behind his current situation: “A life with purpose is the life of a person with a home and homeland—and most importantly, stability and a sense of security. A person then is not condemned to struggle constantly to find enough to eat and drink so they can go on breathing. They can think about more than just survival.”

Abdel Qader fears for his sons’ future. It looms before him in dark tones. Especially now, as Lebanon is plunged into social, financial, and political mayhem and the future has become impossible to predict. In Lebanon, anything can happen. A crisis can lead to a “demographic war” or civil war. The internal situation can rapidly deteriorate. Abdel Qader carries the feeling at all times that he could lose everything from one moment to the next.

This is a fear shared by the 1.5 million Syrian refugees still living in Lebanon—900,000 of whom are registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)—especially within the context of plans to remove Syrian refugees from the country “by legal means.”

On Tuesday, June 21, 2022, during a press conference on the “Lebanon Crisis Response Plan 2022–2023,” Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati urged the international community to cooperate with Lebanon in order to repatriate Syrian refugees. “Otherwise,” he warned, “Lebanon will have a situation that is not desirable for Western countries, which is to work to get the Syrians out of Lebanon by legal means, through the firm application of Lebanese laws.”

This and similar statements stoked concern among the country’s Syrian refugees, who often have no place to return to in Syria, and/or fear for their lives and the safety and well-being of their loved ones were they to return to a country from which they fled. Abdel Qader’s appeal to the international community, including the prime minister of Lebanon: “Send us to our homes in Syria. But help me rebuild my ruined house in al-Qusayr. Provide us with a security guarantee that we will be safe from the Assad regime—that we will not be arrested or murdered. That we will be able to return to our homes and our homeland. Then we will no longer stay in Lebanon.”

Multiple international institutions have issued reports establishing that, at the present time, to return refugees to Syria would place their lives and well-being at risk. Mines are prevalent in many areas, entire cities are largely destroyed, and there is a lack of access to clean drinking water and medical care. Additionally, in a report from 2020, the German Federal Foreign Office stated: “Syria is not a safe place because returning men between the ages of 18 and 42 must enlist in the army within twelve months—or else face a prison sentence for having left their country.”

Refugees who voluntarily returned to Syria, from Lebanon and Jordan, between 2017–2021, have been subjected to persecution and violations of their human rights. They have been abducted, imprisoned without due process, tortured, and extrajudicially executed.

Human Rights Watch has called for an end to forced deportations of Syrians from asylum countries to any part of Syria, noting in a report: “While evidence of widespread and ongoing violence [and] active hostilities might have decreased in recent years, the situation is fluid and relative periods of stability fail to meet basic conditions for safe, dignified, and durable return.”

This is the context which prevents Syrian refugees from considering returning to their country at this time. Syrian citizens meanwhile continue to lose their homes to bomb and rocket attacks. These individuals are stripped of any feeling of security and stability, and cannot predict what will happen to them next.

Al Waled Khalid Yahya

Beirut, Lebanon