Escape

Escape is rarely a choice. Escape becomes a necessity. It is a surge of the remaining will to live.

Then, one day, the moment comes when you finally decide you have arrived somewhere. It is a point along the road. Sometimes random. A house, a tent. Your life is safe for the time being—but what else remains, what has been salvaged?

You try to make the best of life, to create a new home, though fragmented memories remain of the place from which flight was necessary.

Anywhere is safer than back there.

Often makeshift, the new home is only an illusion…

Charków, Ukraina 2022.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska dla „Gazety Wyborczej”

Charków, Ukraina 2022.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska dla „Gazety Wyborczej”

When you ask me what I remember of my home in Syria, I remember a wooden cupboard filled with new crockery and beautiful glassware we received on our wedding day.

They were for us to use in the future.

And then a missile hit our house and everything was destroyed.

Kurdystan, Irak, 2019.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska

Idlib was the last place where I was viewed as a Syrian citizen. The moment I crossed the border into Turkey, the world assigned me the status of “refugee.”

I decided it was time to flee like the others. However, this was not a straightforward decision. On the contrary. How can you leave the place where you grew up and know so many people? How can you just part with your memories and go someplace where you do not even speak the language?

My name is Ahmad. As many know, it is a common name in the Middle East. But who cares? What does it matter? I had the same reaction when my grandfather once told me: “Grandson, everything in life can be gained or lost—except your name. It is up to you to make it a good or bad name.”

At the time, I did not pay any attention to the meaning of his words. Today, I lost my grandfather, and I understood what he meant.

When it was time to pack my bags and any essentials, I decided to bring nothing but the one thing that could never be taken from me or lost: my NAME.

Eido, jezydzki pasterz z Szingalu. Uciekł z rodziną przed bojownikami tak zwanego Państwa Islamskiego. Dziś mieszka w obozie uchodźczym w Kurdystanie, Irak, 2019

We escaped.

We built a house here from scratch. Of mud and clay, like in the old times.

A Syrian family in 53267-01-033 refugee camp in northern Lebanon. From left: Mahmoud, Muhammad, Zikiah Abdallach Faraj, Nuur Al-Huda, Shahad, Aya.

“We have this tent for a home. In Syria, we lost everything. Here, at least, we have a few meters of fabric to shield us from the wind, rain, snow, and sun.”

We have this tent for a home. In Syria, we lost everything.

Here, at least, we have a few meters of fabric to shield us from the wind, rain, snow, and sun.

Hawaje, nieformalne obozowisko namiotowe, w prowincji Al-Mafrak, Jordania, 2019.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska

This is what our life [in the camp] looks like. A state of stagnation.

The next night, after spending one day in that hell, I asked: “How long will we stay here? A week? A month? A year?” I asked this question in my mind each night. It deprived my tired eyes and body the sleep they needed after struggling all day to resist heat or cold while waiting in the long lines for food and water, for the toilet, to see a doctor and receive obscure medicine.

One time, I was with Rafaat, our youngest son, in a house with a staircase.

He began crying. “Mama, what is this?” he asked me.

Rafaat had never seen a staircase in his life.

He had no idea what the stairs were for. That the stairs led upwards. Rafaat doesn’t know that doors have handles, what the handle is for. He cannot comprehend the concept of a house, what the word “house” means. He doesn’t know what a bathroom is. What heating is. He was three months old when we fled Syria. Now he is ten years old.

Obóz 53267-01-117, Północy Liban, 2022.

The Worst of All Possible Worlds

I am standing in front of the tent. A group has gathered by it. Food is being cooked over the fire in a large pot. Twenty people live here together, eating one meal per day. A thought runs through my mind: We live in the worst of all possible worlds.

In the same camp, a short distance away, Nora Fajzer shows me how she prepares water to bathe her children. She puts a pot on the hearth, kindles plastic, some sponge, and plastic bags, places a piece of dry wood underneath. Yes, she burns garbage. It is all she has. Even worse, the camp lacks clean water. There is no clean water at all in the Mayas camps, 53267-01-117, 53267-01-033, in northern Lebanon, same as there was no water in Iraq—in Debaga, Khanke, Domiz, Hassan Sham—or in Jordan.

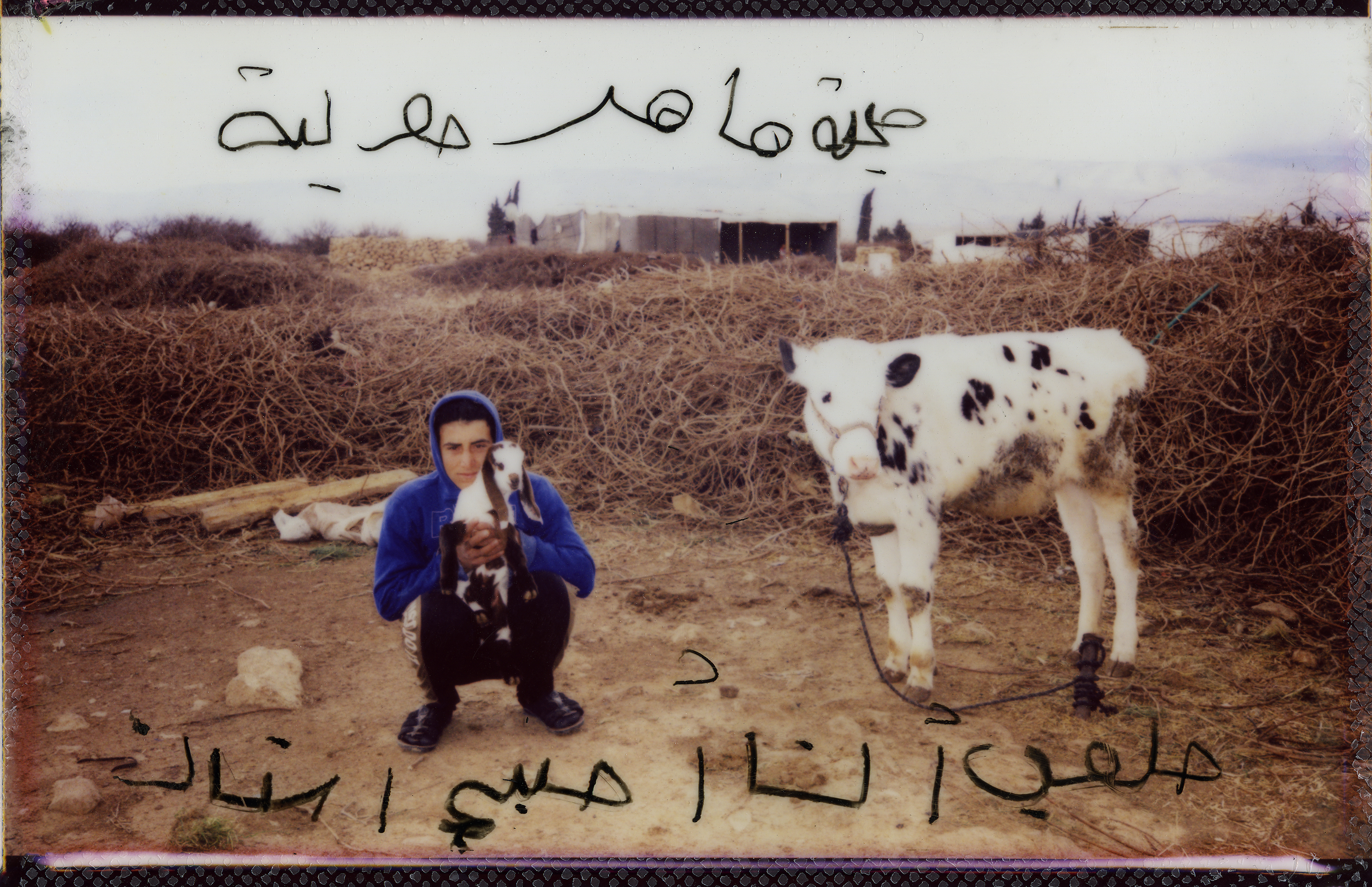

On a Polaroid I took of him, Maher wrote that he would like to go to school because knowledge is the future, and here there wasn’t one. I learn that of the seven children living in Mahmoud’s pink tent, Shahada is the only one attending school.

Refugee camps are usually in the middle of nowhere, far from big cities. Even were a child to have the option of attending a school, he or she would be faced with a daily trek of many kilometers, in scorching heat, against strong wind, in the snow and bone-chilling cold.

Obóz dla syryjskich uchodźców, Liban, 2022.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska

Everyone has a hero inside. Not the ones from Hollywood with fancy costumes, superpowers, and fan clubs, but the unique hero inside of you that is able to get you through the hard times, that makes you the unique person you are, giving you the strength to overcome setbacks. This doesn’t mean that there aren’t times when you cry yourself to sleep at night. We live in a cruel and bloody world, and we have to deal with disappointments and obstacles. But you will be able to rise to try again. I hope one day you’ll be able to feel grateful for the suffering as well. That you will be able to embrace it.

Obóz Mayas, Liban, 2022.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska

We have lived in this camp for ten years. We no longer remember what home is.

Would you call a place “home” if your children slept at night with rats running around them and insects biting them?

Liban, 2022.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska

I wish I had the opportunity to learn.

To go to school to have a future.

Bejrut, Liban, 2022.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska

It is 2022. Western nations are striving to improve their economy, technology is developing, 5G is widely available, missions to the Moon are underway.

And yet we, in Lebanon, live without electricity in our homes.

Charków, Ukraina, 2022.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska dla „Gazety Wyborczej”