The Road

The road from Beirut to Europe goes through Syria. Idlib seems not so far away from Beirut. Just 337 kilometers. From Idlib, you head to Turkey. Even closer: just 52 kilometers. Like so many before you, you find a way to obtain a visa and a passport. You pay to navigate the next points en route to your destination. From the border of Syria and Turkey to Izmir: 1,100 kilometers. Under the cover of darkness, you cross multiple borders one after another. Your identity is irrelevant. Your name has not changed, but the world now refers to you by one word: migrant. One of millions. Next you purchase a plane ticket, or get yourself a space on a boat to Greece (418 km). Then—via Macedonia (854 km), Serbia (432 km), Croatia (393 km), and Slovenia (138 km)—you reach Vienna (423 km). Finally: Berlin (682 km).

This is the route a young man in Beirut broke down for me. 4,829 kilometers of road. Some of those kilometers in a car, some covered on foot. You have to crawl under barbed wire, cross the sea… He walked, in search of a safe place along the way. Getting lost in the forest, he was afraid. He suffered from hunger, thirst, injuries to his legs.

4,829 kilometers. Writers publish books about such journeys. They win awards and are invited to literary ceremonies. Meanwhile, a migrant ends up sealed off in a “closed” camp. They are insulted, mocked, spat on. But they keep going.

4,829 kilometers of hope.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska

I wasn’t scared about crossing the sea without knowing how to swim. It was taking care of my brother that was the hardest thing. I still hear him screaming in my ear: “Ahmad, we are drowning!”

Because of the big waves, the boat was going wildly up and down and water soaked his bottom. How could I, scared as I was, calm down a child in such a situation?

We knew that thousands of people had already drowned in the sea.

Syria 2012.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska

We have reached a point of suffocation as a society. Neither you and your family nor anyone else can continue living here…

Poland opened its borders to Ukrainian refugees and welcomed them with open arms.

And yet a Syrian simultaneously escaping the same Russian bombs, same as a Ukrainian…

Bejrut, Liban, 2022.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska

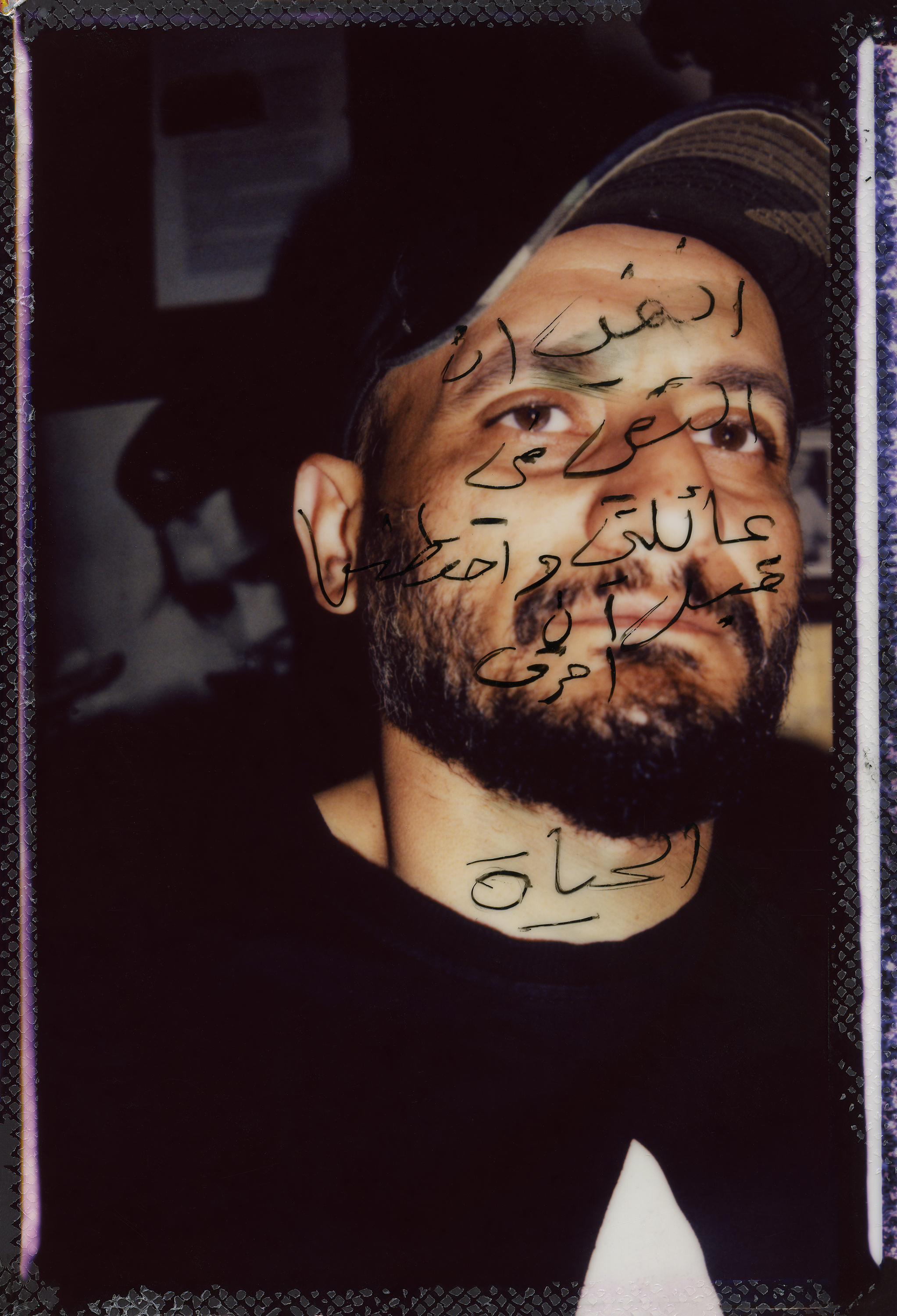

I am tired.

I yearn to see my family before I die. I want to hug them.

My mobile phone is everything to me at this point: my memory, my family album.

Remembrance of what we could not experience together.

Through it, I watch my son, who I cannot hold in my arms, grow up.

Khalid – Libańczyk mieszkający i pracujący w Bejrucie. Jego żona przebywa w Szwecji wraz z ich dwuipółletnim synem. Khalid jeszcze nigdy nie widział swojego dziecka. Rządy libański i szwedzki wielokrotnie odmówiły Khalidowi przyznania wizy i rozpoczęcia procedury połączenia rodziny.

Na filmie Khalid rozpakowuje paczkę wysłaną przez jego żonę ze Szwecji, w środku znajduje pukiel włosów swojej żony i śpioszki swojego syna Eliego, dzięki którym może poczuć zapach swojego syna.

film: Khalid, Liban 2022

Khalid

Khalid is a Lebanese living and working in Beirut. His wife is in Sweden with their son, Eli, who is two and a half years old.

Khalid has never seen his child, except in photographs and videos. The governments of Sweden and Lebanon have repeatedly refused to grant Khalid a visa and to initiate the family reunification process.

In the video, Khalid opens a package sent to him by his wife from Sweden. Inside, he finds a lock of his son Eli’s hair and a onesie. With these in hand, he can smell his child.

I was born in 1948, the year of the Nakba. My homeland is Haifa in Palestine. When I was just forty days old, my parents took me to Syria. I once had a house. I worked for the UNRWA. I studied law. Now I am seventy-four years old. One day, I looked up and found I had nothing left.

I am old and weak. My children have gone. One daughter flew from Lebanon to Egypt, then made it across the water to Italy. It took six days. My second daughter, Suad, arranged transport for her from Italy to Austria. From Austria she went to Sweden, where she stayed. Their brother, Bassel, left the country by plane. He was arrested in the Netherlands. He was trying to reach his sister in Austria, but he did not succeed.

My husband’s parents died at sea on a journey from Palestine to Jordan when he was three months old. Drowned. Many decades later, history came full circle. On September 6, 2014, my husband drowned in the Mediterranean Sea aboard a ship carrying 200 Palestinians.

Liban, 2022.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska

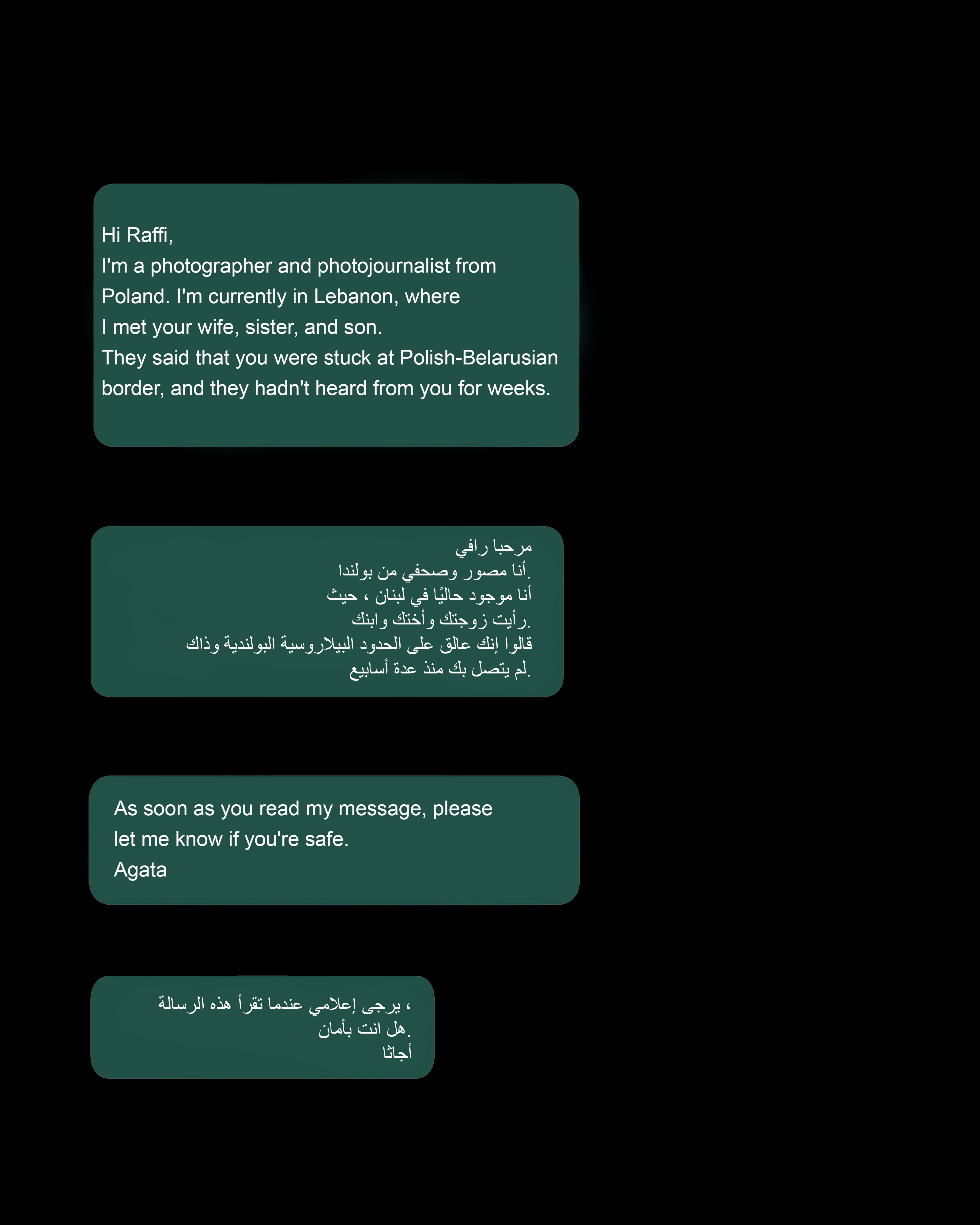

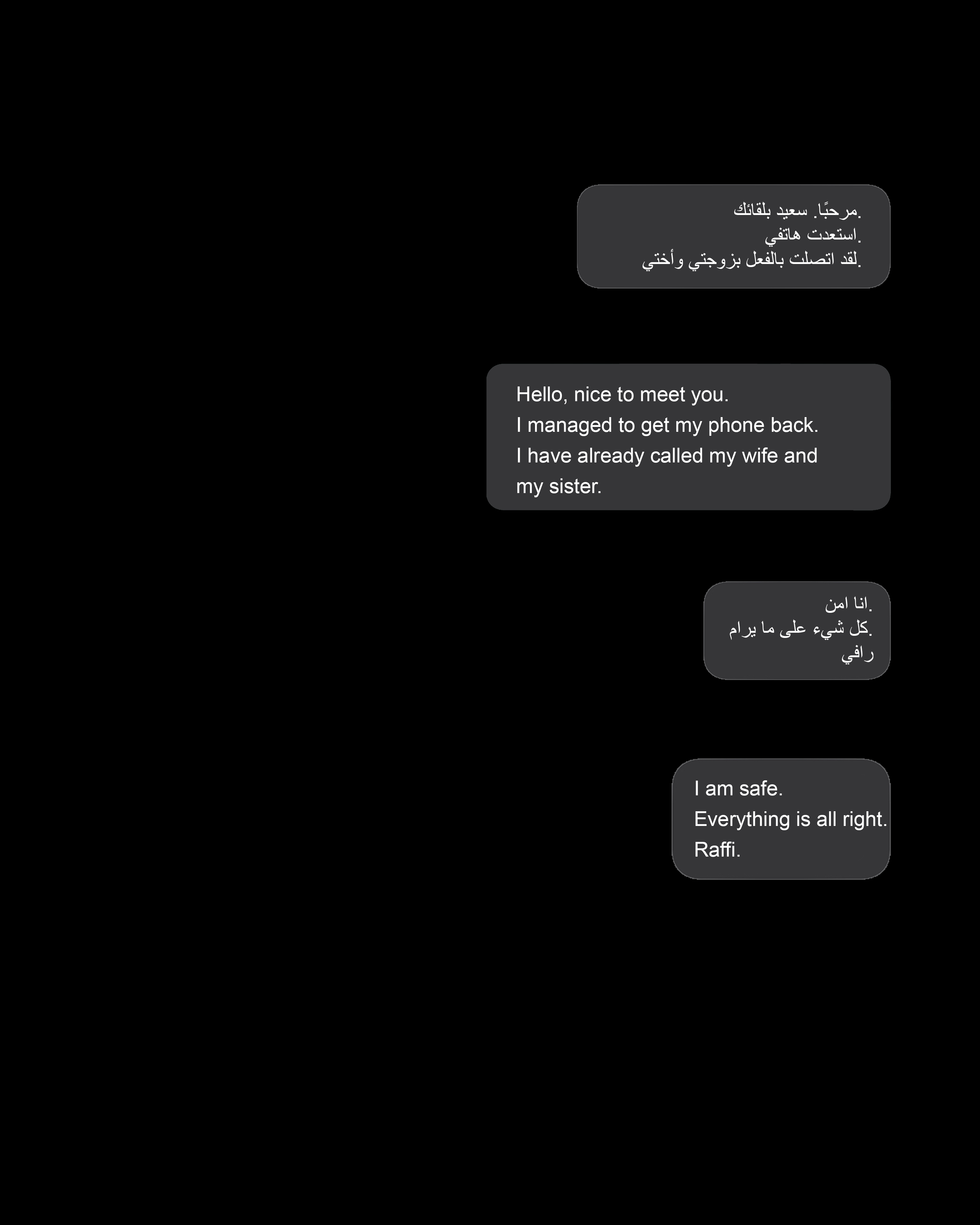

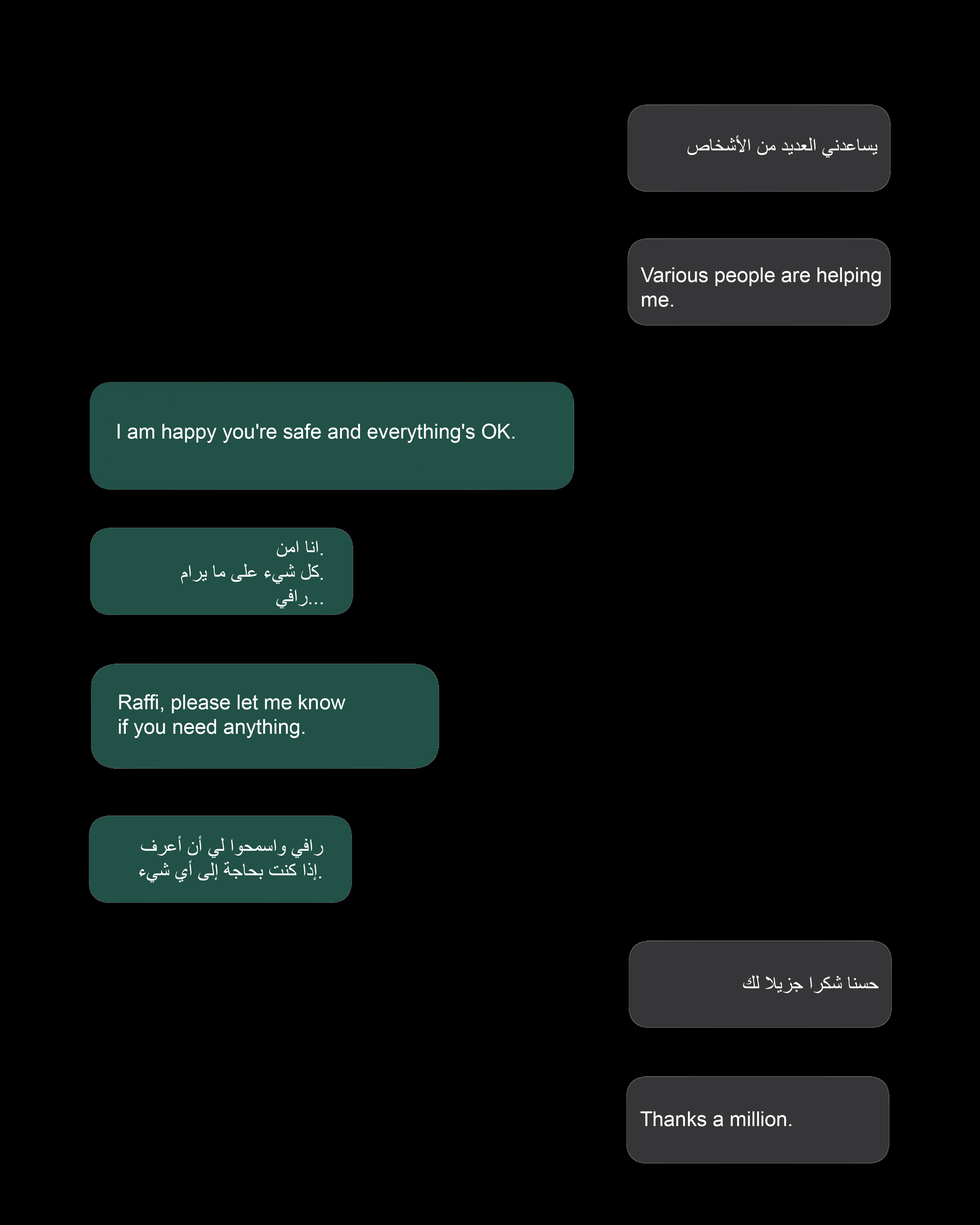

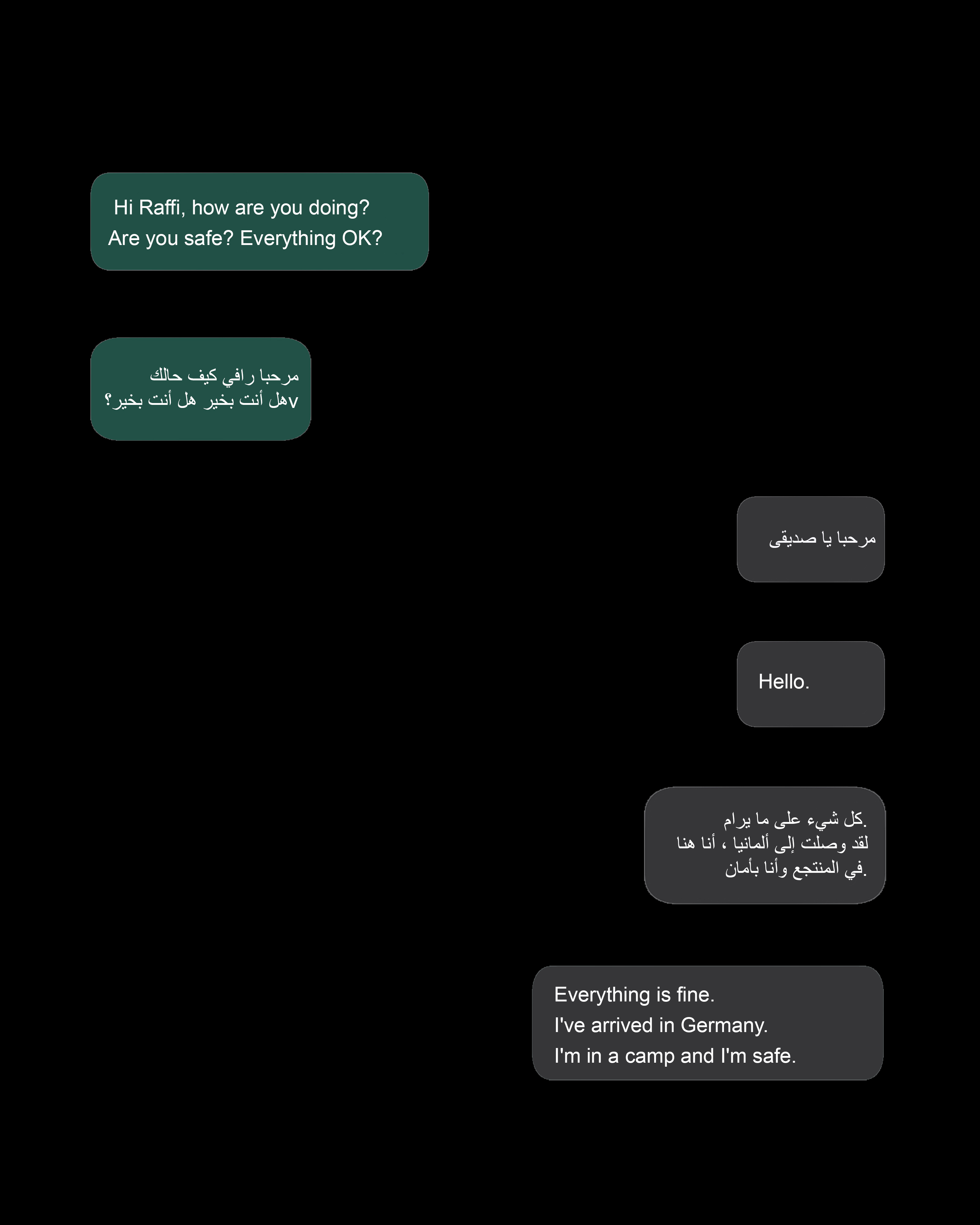

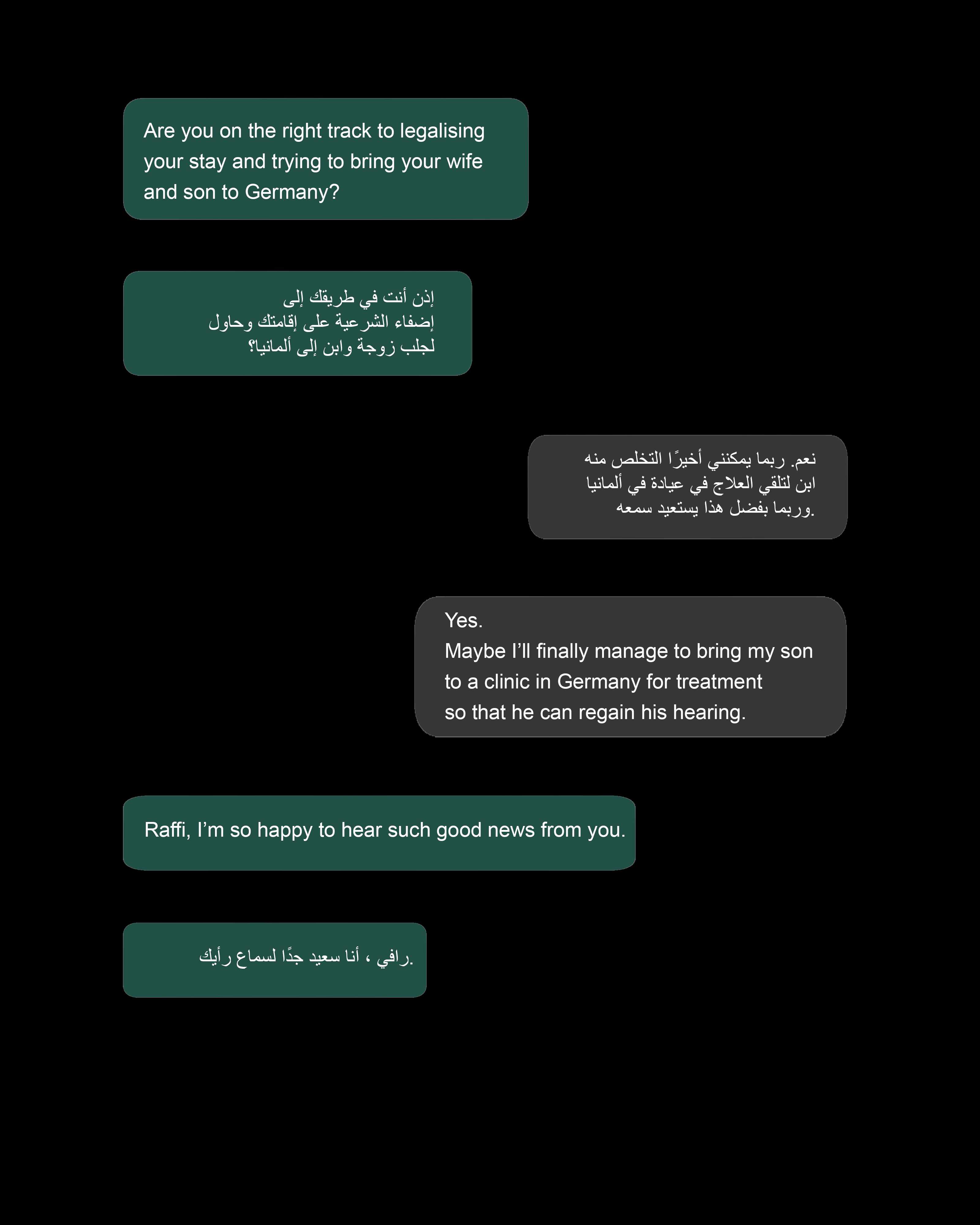

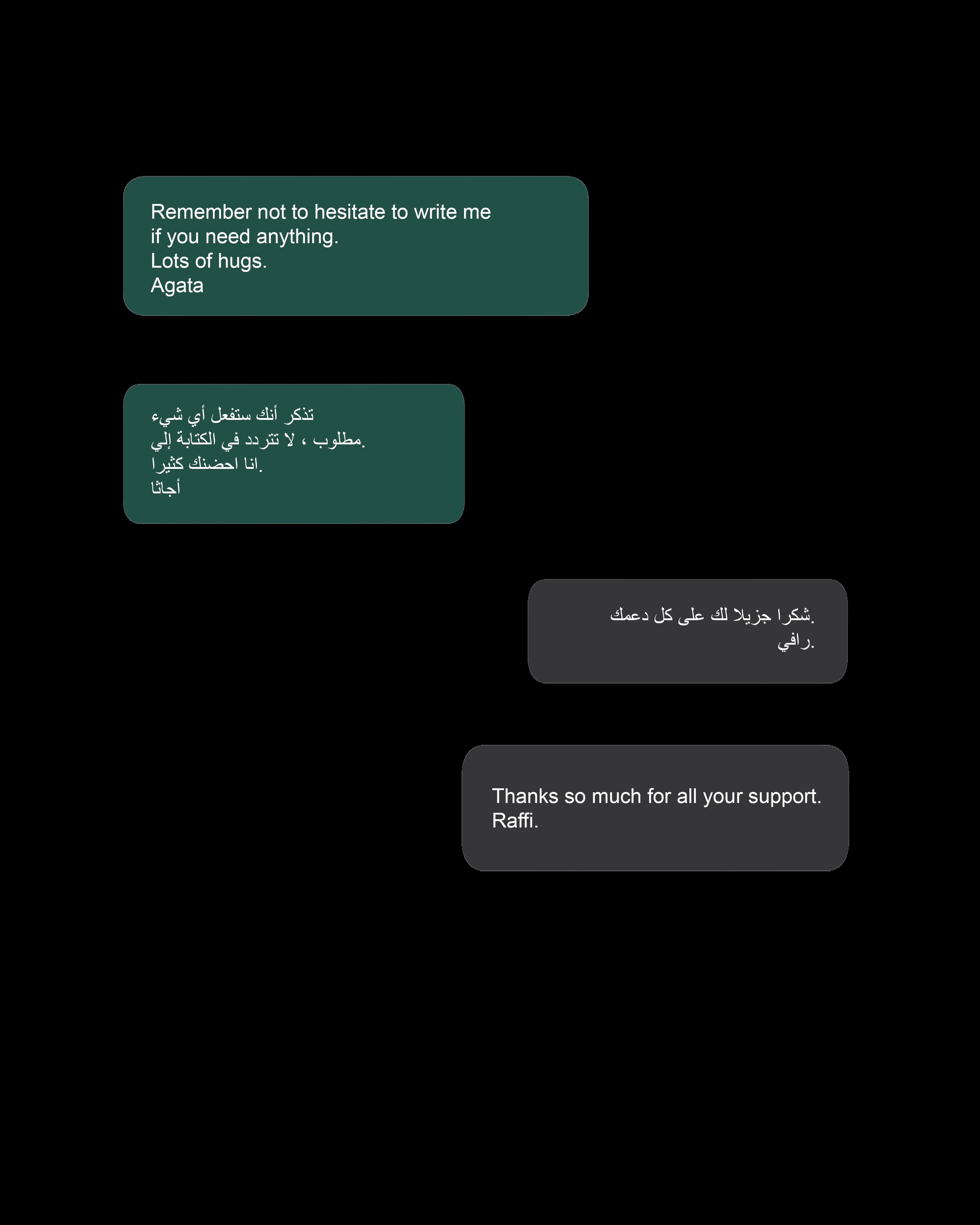

Raffi

In the picture are Raffi’s wife, son, and sister. Raffi’s family, having fled Syria together, is currently living in Lebanon.

Raffi spent several months trying to cross the border from Belarus into Poland, and from there to make it on to Germany.

He was forced back across the Polish border repeatedly (“pushback”). Finally, after a dozen attempts, he managed to reach Germany, where he began proceedings to legalize his stay in Europe.

He plans on bringing his family to Europe, and to have his son’s hearing treated in a German clinic.

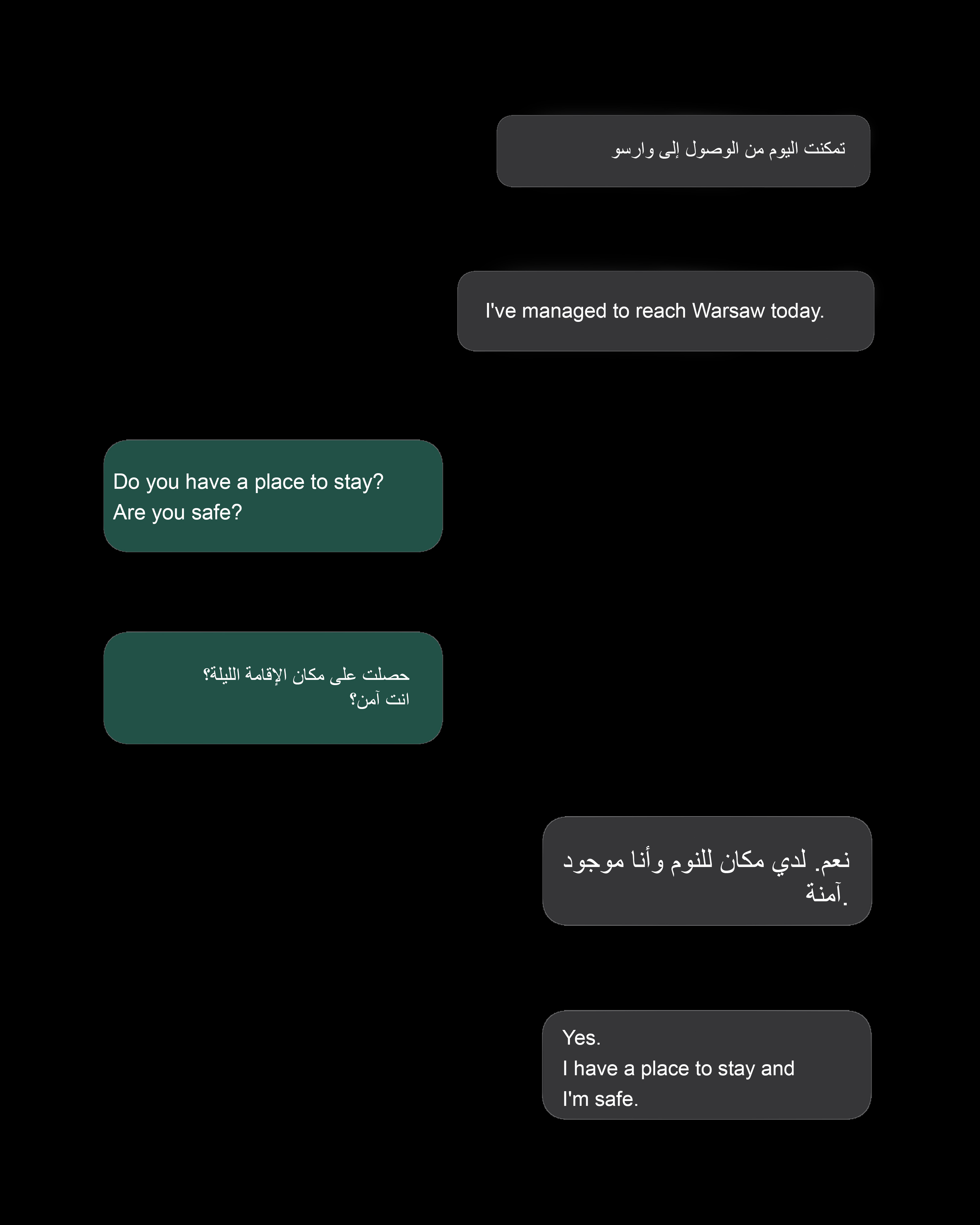

VR Shamsul Rahman, Afgańczyk mieszkający w Warszawie.

Shasmul przez lata pracował dla amerykańskich firm informatycznych w Afganistanie. Został zmuszony do ucieczki ze swojego kraju kilka miesięcy przed upadkiem rządu Aszrafa Ghaniego, bo zaczęto grozić mu śmiercią. Przekroczył granicę polsko-białoruską, dzięki pomocy wolontariuszy znalazł mieszkanie w Warszawie. Jego marzeniem jest sprowadzenie żony i czwórki dzieci bezpiecznie do Warszawy.

In the forest, we came to the posts marking the border between Belarus and Poland. The smuggler lifted the barbed wire with his hand. “Go,” he said. “That’s where your future is.”

* People sometimes ask me: Why did you choose Poland?

I did not choose Poland. Poland chose me.

My friends all think I make good money. In fact, I send everything I earn to my family and those in need in Afghanistan. I pay bills and have something left over for food. I don’t require much. I like to help out, and I don’t squander money on indulgences. My Afghan friends say this is the reason I don’t have friends: because I wear second-hand shoes, because my beard isn’t fashionably trimmed, etc. But I don’t need any of that.

Centrum Warszawy, Polska, 2016.

Fot. Agata Grzybowska

I will move forward with closed fist and open mind

The day that everyone will be free

Like ocean tides

Or rays of sunshine on an iceberg